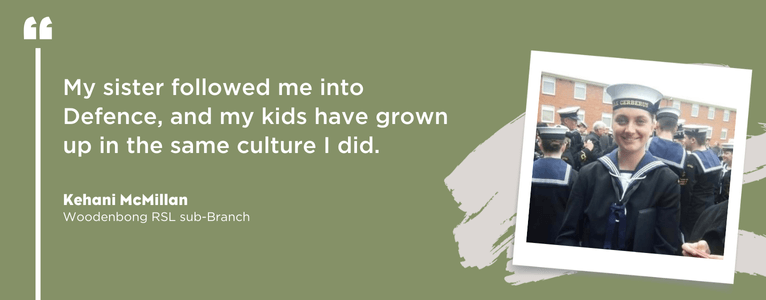

Kehani McMillan in the spotlight: A veteran’s life comes full circle

What began as a gap year became a career-defining journey for former Navy marine technician Kehani McMillan.

As told to Girard Dorney

At a glance:

- Kehani McMillan grew up in a town that was deeply respectful of service.

- After being medically discharged, she experienced regrets about whether she’d accomplished what she wanted.

- She believes that the RSL NSW community is crucial for veterans’ wellbeing, and is now Treasurer and Secretary of the Woodenbong RSL sub-Branch.

I grew up in the small town of Woodenbong, where there are local families who have been here for generations. Because so many of them served in World War I and World War II, almost everyone has at least one or two relatives who are veterans.

Every ANZAC Day, we present a slideshow of the pictures and service records of all the veterans and current Defence personnel from the area. You could be the toughest person in the world, and I guarantee it would bring a tear to your eye.

I never dreamed of joining Defence; I’d always wanted to be a primary school teacher. However, when I finally got to year 12 and looked ahead at the prospect of another four or so years of study, my heart sank.

I decided to do an ADF Gap Year, and my mum and dad were very supportive; Dad even took me to the interview with the recruitment officer. I was adamant about my goal. “Army nurse,” I told them. “I want to be an Army nurse.”

The recruiter, though, spoke in glowing terms about the Navy and how I’d get the chance to travel. Soon enough, I came out of the interview and told my surprised dad that I was signing up for the Navy instead.

A gap becomes a career

I enjoyed most of my initial experiences, but there was a lot of hatred for gap year recruits, especially women. We were called “rent-a-Navy”. It was a struggle. That being said, people gave me respect because I treated them with respect.

After finishing my initial training, I was told to join the crew of the HMAS Kanimbla. So I travelled to where it was docked, but I didn’t even get to step onboard. A crew member of the HMAS Gascoyne, a minehunter, had become sick, and they were looking for an emergency replacement. I had to fly to Fiji to join them. It was my second plane flight ever – at the age of 18 – and my first outside the country.

From Fiji, we went to the Solomon Islands, where we began clearing Japanese mines left over from World War II. Each minehunter was responsible for exploring its own small area. A remote-controlled submarine searched the seabed. Once a mine was found, the clearance divers attached explosives. The blast would rock the boat and you could see waves on the water.

Thinking back on it now, I grew up honouring our local veterans who served in World War II. Later, when I was serving, I dealt with mines that were intended for them.

At the end of my gap year, I decided to remain in the Navy and train to be a marine technician, which is the equivalent of a diesel mechanic.

Twists of fate

If Defence is male-dominated, the marine technician part of the Navy is especially so. There were a couple of other women in the engineering department. They were relentlessly perved on and things were said to them that shouldn’t have been. I never got any of that, because I set boundaries from day one, so they knew it wasn’t on.

It’s a bit sad that you have to adapt like that to a workplace.

My partner, now my husband, is a diesel mechanic in the civilian world. He was supportive, and followed me throughout my different deployments.

My goal was to serve six to 10 years, but four years in I had a catastrophic knee injury. There was a lot of nerve damage they couldn’t fix. After surgery, I was put into an office role as part of the Fleet Support Unit in Darwin. I hated not doing what I signed on to do, and I felt isolated from my peers. and, eventually, I was medically discharged.

I definitely had regrets. I felt like a failure; I hadn’t completed what I’d set out to. But my transition out of Defence was otherwise smooth. My partner and I moved back home; I started handing out my resume, and I got a job in real estate.

I did that for a little while, then my husband and I started a family, having a girl and a boy. I now work in an office role for a diesel mechanic business we set up together. My Navy experiences prove very helpful with ordering parts and understanding the basics of the engine I’m looking at. I joke that admin must be where I belonged all along.

Connections to the past

I joined the Woodenbong RSL sub-Branch in 2018. Being part of the community a sub-Branch provides is a comfort. I can talk to my husband about an issue, but he may not understand the lingo or experiences. But veterans will get me straight away.

My belief in the importance of the veterans’ community is why I became the Treasurer and Secretary of the sub-Branch last Christmas after being asked.

My sister followed me into Defence, and my kids have grown up in the same culture I did. We visit military museums during the holidays; we honour the minute silence on Remembrance Day; they’re always respectful when hearing veterans’ stories; and my daughter is always keen to sing the national anthem on ANZAC Day.

Now, every ANZAC Day, my children see their mother and aunt in the slideshow.

Whether you’ve served for a single day or decades, RSL NSW welcomes veterans of any service length and background to join the organisation. Access support services and become part of a like-minded community of peers by becoming a member of RSL NSW.